Dia Cohen

Waldorf School of Louisville Article for 8th Grade Capstone Project

FOUR UNIQUE FATES

THEY WERE REGULAR PEOPLE. HOW DID THEY REACT TO THE RACISM IN AMERICA? WHAT CAN WE DO TODAY?

As an African American from Colombia, I arrived in the United States recognizing prejudice and enduring it first hand. Racism in the United States is not as bad as what I experienced in Colombia, yet I have always wondered if there will be a time of equality for all races. I never did anything about the unfairness in our world because I assumed that regular people like me couldn’t improve the inequity in the world. However, after the recent events in Louisville involving police brutality, I was inspired to consider… What happens if I do want to address prejudice in this world? Why was this ongoing discrimination passed down by my parents, teachers, and other adults? Was I destined to live with the tyranny that the African American race suffers? I don’t want to live in a world where racism is everywhere I turn. I looked for people who inspired me to work for a change, who helped me understand why there needs to be a change. I did some research on the Civil Rights movement. My goal was to understand what it was about and what it represented for African American history. I discovered four Civil Rights participators and was able to personally interview one of them. These four people were not famous Civil Rights leaders. They were regular people like me and probably you. They were good people and lived by the law of justice and compassion. They blessed their communities with their small but courageous acts. For me, they have shown me that a regular person like me and you do have the power to speak and act as our way of reflecting that a future charged with prejudice and ignorance is not what we want.

Septima Poinsette Clark

“The air has finally gotten to the place where we can breathe it together.”

Septima Clark was a black American educator. Septima saw that African Americans were not able to vote or enter voting polls because they could not read or write, so she made it her responsibility to guide illiterate people on how to exercise their voting rights to engage themselves in the act of empowering African Americans. To vote, a voter had to be able to read the ballot and write their signature themselves, which was a barrier for many African Americans who were sometimes former slaves and had been forbidden to learn to read and write. Clark was born on May 3, 1898, in Charleston, South Carolina. In 1916, she graduated from secondary school and taught as a teacher throughout South Carolina for more than thirty years, including eighteen years in Columbia, and nine in Charleston. Around the 1930s’, Clark studied under W.E.B.Du Bois, an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and civil rights activist who taught economics at Atlanta University. In 1946, Clark received a Master of Arts degree from the Benedict College in Columbia, SC.

Throughout the 1940s, Clark worked as an educator but was also associated with the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), which is one of the largest, non-profit, multicultural organizations dedicated to eliminating racism, empowering women, and fighting for justice (https://www.ywca.org/about/). Clark also participated in a class-action lawsuit filed by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) that influenced equal wages between black and white educators. Clark participated by attending their meetings and leading her students to protest along with her. In 1956, South Carolina established a law forbidding city and state employees from working with Civil Rights associations or else they could be fired from their jobs. Unfortunately for Clark, after forty years of teaching, she lost her job as an educator because she refused to leave the NAACP.

By the time of her firing in 1956, Clark had begun to lead classes during the summer at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, a grassroots education center dedicated to social justice. In 1954, Myles Horton, founder of Highlander Folk School, hired Clark full-time as Highlander’s director of workshops. Clark believed that “knowledge could empower marginalized groups in ways that formal legal equality couldn’t”- (Wikipedia). Clark taught people basic literacy skills, as well as their rights and responsibilities as US citizens. She also taught African Americans how to fill out voter registration forms, acknowledging that many black people didn’t know how to write.

Clark worked with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, and with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to coordinate and support nonviolent protests. Clark continued to serve as an educator and leader of civil rights until she died in 1987. She left a life-long legacy as both a civil rights activist and admired educator. Clark’s way of addressing racism was through education. She taught people how to use their voices to participate in the ongoing fight against racism.

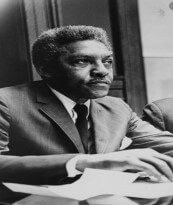

Bayard Rustin

“Let us be enraged about injustice, but let us not be destroyed by it.”

Bayard Rustin was an American leader in the civil rights movement, an adviser to Martin Luther King, Jr., and the main organizer of the March on Washington in 1963. He also participated in marches that supported socialism, nonviolence, and gay rights.

Bayard Rustin was born on March 17, 1912, in West Chester, Pennsylvania. He was raised by his maternal grandparents, Julia and Janifer Rustin. Growing up, he was led to believe his mother to be his sister to shield his family from the embarrassment of a young, unwed mother. His grandparents were local caterers who raised Rustin in a large house. Rustin’s grandmother, Julia, was a member of the Quakers, now known as the Religious Society of Friends or Friends’ Church. Julia was also a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and she was well connected to leaders of the NAACP, such as W.E.B. Du Bois. She often brought them to visit her household. Rustin grew up surrounded by people who were fighting for equality and justice.

Bayard Rustin began opposing racial segregation in high school through peaceful, nonviolent protests organized by different civil rights organizations. He was jailed in 1944 as a conscientious objector to World War II, which meant that for personal reasons, he refused to serve in the military. During his two years of prison time, he protested against the segregated facilities. Even from inside the walls of the prison he continued the fight for justice and equality. In 1948, after his release from prison, Rustin traveled to India to learn the peaceful strategies of civil disobedience that Mahatma Gandhi so effectively used. However, Gandhi had been recently killed so Rustin used his time in India to visit other independent leaders from Ghana and Nigeria still hoping to have a deep understanding of the nonviolent tactics Gandhi taught the people in India.

Rustin started working with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1955. He shared his ideas of peaceful protest with him. Eventually, Rustin became King’s advisor, as well as a key strategist in the broader civil rights movement. Rustin was sought out by many throughout the Civil Rights Era because of his high degree of knowledge about pacific protests. However, his biggest contribution to the movement was on August 28th, 1963, when all that he learned about peaceful protest came together and formed itself into the March on Washington. All the violence that could enfold this day concerned Bayard, hence he worked with the hospital and police to prepare everything at the March in case of any brutality (TEDTalks). He was successful and the March on Washington was a peaceful, non-violent event. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his famous, ‘I have a dream’ speech. That day nearly a million people gathered in front of the National Mall demanding an end to prejudice, segregation, violence, and the economic boycott that black people faced. None of this would have been possible without the guidance of Bayard Rustin. Despite all his knowledge, insights, and utility as an advisor to King other organizers of the movement did not like the idea of Rustin at the forefront of The Civil Rights Movement because he was homosexual (though many outside the inner circle did not know). In the 1980s, Rustin publicly came out as homosexual and was effective at drawing attention to the AIDS crisis. Rustin continued to speak out and organize protests that fought against injustice until he died in 1987.

In 2013, President Obama posthumously awarded Bayard Rustin the Presidential Medal of Freedom, an award given by the president to someone who has contributed to the security or national interest of the United States, world peace, and other public or private things performed out of generosity for the interest of America. Bayard Rustin’s life’s commitment was fighting for equality through peaceful means, persistence in the face of resistance, and learning the non-violent ways of others who also fought for equality helped move the Civil Rights Movement forward. His reaction towards racism reminds us today to take action, to learn, and to peacefully fight for what we believe is right.

John Robert Lewis

“One person with a dream, with a vision, can change things.”

John Lewis was an American statesman and civil rights leader who fought for African American equality and justice until his death in 2020. Lewis was born on February 21, 1940, in a rural area of Troy, Alabama. As a child, he picked cotton on his family’s farm. He hated working on the farm, enduring the long hours under the sun and he didn’t want that future. Lewis aspired to go to school and become a minister.

Lewis had hopes that he would be able to attend Troy State College (now Troy State University) which was close to his home but where only white students could attend. Although this meant that Lewis couldn’t work on the family farm, his mother encouraged him to apply. Lewis submitted his high school application but never heard back from the school. Frustrated but not defeated, he wrote a letter to Dr. Martin Luther King asking for his help to desegregate Troy University.

While waiting for King’s reply, he was accepted to a small college in Nashville, Tennessee, where he went to school. To Lewis’s surprise, King later invited him to Montgomery, Alabama to meet in person. When he met up with King, he was advised to return home and ask his parents for approval to join Martin Luther King in filing a suit against Troy State to allow him to be admitted to the school. Lewis’s parents disapproved of this lawsuit so he continued to study in Nashville, TN.

In Nashville, John Lewis got involved in many movements whose goals were to desegregate places around the South. As he protested he was able to see Martin Luther King many times. King taught him the discipline of non-violent, peaceful protesting, that every human being is valued, and to love your enemies as your friends (TEDTalks) In Montgomery, listening to Dr. Kings’ speeches, hearing about Rosa Parks’ actions, and working with other leaders in the movements Lewis was inspired to do what he called ‘good trouble’.

John Lewis accompanied Dr. King to many places where they could make people aware of the injustices towards black people. In an interview with Bryan Stevenson (founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, fighting poverty and challenging racial discrimination in the criminal justice system) Lewis explained how he was the youngest speaker at the Washington, DC Freedom Riders protest on May 4, 1964. This was the massive political protest where people gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial to advocate for the civil, economic rights of African Americans.

“I was determined to inspire young people, another generation. And, when I looked out and saw that sea of humanity, I said to myself, this is it. I must go forward.”

When Dr. King was assassinated in 1968, Lewis was despondent but moved forward. John Lewis first ran for public office in the 1970s because he thought that this was the best way to advocate for black people and work for change. He also became the director of the Voter Education Project (VEP), which was an organization throughout the Southern states that administered voter education programs and voter registration drives. Lewis held his position as director of the VEP until 1977. In 1986 Lewis was elected to the United States House of Representatives from Georgia’s fifth congressional district and served with distinction until his death.

“How do you want to be thought of? How do you want to be talked about?” asked Bryan Stevenson. Lewis replied, “I don’t think I would have much to say about it; but it would be– He tried to make a better society, a better world, helping to liberate and free people, helping to save people, to move people to a different and better sense of humanity.”

John Robert Lewis died on July 17, 2020, in Atlanta, at the age of 80, from pancreatic cancer. Throughout his life, Lewis demonstrated how to fight for equity through nonviolent protest. His actions were portrayed by his powerful ethical code: Love unreservedly. A few weeks before his death, mustering all his strength, Lewis was able to walk with protestors as part of the Black Lives Matter movement, his last walk for racial justice. He was proud and very hopeful that they would continue to make ‘good trouble’.

John Lewis’s way of protesting against racism was to acknowledge every person’s worth, to respect all people, to never give up on anyone because you are trying to teach them what love and kindness are with your actions. His forgiving soul reminds us today that love and mercy are possible, just like he forgave those who physically and mentally hurt him because of his race. Despite everything he had witnessed and experienced Lewis was capable of anticipating a brighter future.

“I’m very hopeful. I’m very optimistic about the future.”

- John Lewis

Dallas Thornton

“If you believe in something and you see it going on then you participate.”

I had the opportunity to interview Dallas Thornton and gained many insights from our conversation. Thornton is one of the few Civil Rights fighters who are still with us today. He was one of the many Civil Rights fighters whose participation and devotion to the movement opened the world’s eyes to the ongoing discrimination and apathetic attitude toward the suffering of African Americans.

Dallas Thornton was born on September 1, 1946, in Louisville, Kentucky. He attended Male High School in Louisville, Kentucky. He recalls that schools in Kentucky, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi were segregated, meaning that black and white students could not attend the same schools.

Thornton cherishes the memory of the countless times when the people who joined the Civil Rights Movement marched in front of his house, demanding justice and equality. Around 1960, when he was in ninth grade, his family got involved in the movement. At that age, Thornton thought it was all scary but he continued protesting for what believed to be right.

“It was a hard decision. Me and all my friends were out there together, we were all going to march together and protest together.”

- Dallas Thornton

By 1968, the movement was able to end racial segregation. Although the continuing bias did not end, Thornton felt triumphant and proud of the power and influence a mass of people could bring to the country. Thornton never thought that there would be a time where there wasn’t racism because there would always be people with different opinions of how the world and its inhabitants should look. He is hopeful that racism can be eradicated in the future. When Thornton graduated from Male High School he played basketball at Kentucky Wesleyan College. In 1968, Thornton was chosen by the Baltimore Bullets in the NBA basketball draft. He was also selected in the 1968 draft by the Miami Floridians, another professional basketball league called the American Basketball Association (ABA).

From 1969-1970, Thornton played for the Harlem Globetrotters, an American exhibition basketball team. They used comedy and basketball to entertain crowds. The Harlem Globetrotters have played more than 26,000 games in 124 countries.

When asked about what it is like to be judged by the color of your skin, Thorton said, “You have to overcome it. Dr. Martin Luther King taught us and preached to us that people will always think that you are not as good as other people, but you are. So you have to believe in yourself, and the color of your skin shouldn’t have anything to do with your beliefs.”

Today, Dallas Thornton at the age of 74, is recently retired from his job as a Career Planner for the Kentucky Youth Career Center, a program that provides educational and career opportunities, as well as job-search assistance for young people, ages 16- 24. Growing up, Thornton felt he was judged inferior and prevented from doing things because of his race but he overcame it by

ignoring other people’s malicious words directed towards his race. After all, he knew he deserved respect because he doesn’t view people as black and white. He views people as humans who are all equal. Thornton was one of the many people whose way to fight against racism was to join the Civil Rights Movement and demand equity for all. Thornton’s courageous move of joining the movement during those scary times reminds us today that “if you believe in something and see it going on then you participate” just like Dallas Thornton has throughout his life.

There are numerous African Americans who freed their lives from the resentment, the brutality, and the hypocrisy that their race lived through for decades. Dallas Thorton, John Lewis, Bayard Rustin, and Septima Poinsette Clark are just four of the many courageous men and women who have fought for equality and the civil rights of African Americans from the early 1900s to now. These four African Americans all took unique paths as their way of reacting to the prejudice in America.

When I was done interviewing Dallas Thornton I asked him if he saw a future without racism. He said, “Well, tell you the truth, I never thought that there wouldn’t be any racism. I wish there wouldn’t be. But there will be racism because there will always be people that are going to say that you are less because of the color of your skin. And, that’s not a white thing, racism is something that is practiced by many races.”

A day later I thought about what he said to me and noticed that I agreed with him. I know this ongoing prejudice is awful and something I don’t want anyone experiencing anymore. But, the hatred towards African American’s has been going on for so long that I do not know if we can change it. Septima, Bayard, John, and Dallas taught me about compassion, dreams, and the power of simple acts. With this article, I hope you remember everything these four people said and did in the name of their community’s benefit and maybe discover how you can take action against the discrimination and racism in America.

WORKS CITED

HISTORY| Civil Rights Movement: Timeline

October 27, 2009. Updated on June 23, 2020Detroit Under Fire: Police Violence, Crime Politics, and the struggle for racial justice in the Civil Rights Era

“Created by the Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab, an initiative of the University of Michigan Department of History and a component of the U-M Carceral State Project’s Documenting Criminalization and Confinement initiative.”

October 2020Wikipedia| History of Slavery

Last updated on September 17, 2020, at 09:26Reinette Jones & University of Kentucky Libraries. Notable Kentucky African American Database (NKAA)

2017-09-13 18:53:20

- Library of Congress

December 11, 2015 - TED Talks| John Lewis, interviewed by Bryan Stevenson

November 19, 2019 - Stanford University| The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute

National Park Service| Septima Poinsette Clark

June 27, 2019Wikipedia| Dallas Thornton

April 15, 2020Stanford University| Bayard Rustin

March 17, 1912, to August 24, 1987DAILY| How Septima Poinsette Clark spoke up for Civil Rights

Written by Erin Blakemore

February 10, 2016

Biography| John Lewis

A&E Television Networks

April 2, 2014, last updated on July 18, 2020Martin Luther King and the March on Washington

Stephanie Watson

Published September 1, 2015Nonviolence Resistance In The Civil Rights Movement

Terp Gail

Published August 2015Biography| Bayard Rustin

Biography.com editors

April 2, 2014Septima Poinsette Clark- Wikipedia

Last edited January 19, 2021TED Talks| Christina Greer: An unsung hero of the civil rights movement February 2019